domingo, 30 de abril de 2017

La historia sangrienta del Día de los Trabajadores por demandar 8 horas de jornada laboral

La fecha del 1 de mayo está asociada a la conmemoración de los logros del movimiento obrero. Pero el 1 de mayo se celebra como el primero de mayo en la mayoría de los países del mundo como un antiguo festival de primavera. En el Reino Unido e Irlanda el día festivo no se fija el 1 de mayo, sino que se celebra el primer lunes de mayo.

La fiesta también se conoce como Día del Trabajo o Día Internacional del Trabajador y está marcado como un día festivo en más de 80 países, pero hay una historia sangrienta de cómo el Día de Mayo se convirtió en un Día de los Trabajadores. La fecha del 1 de mayo se utiliza porque en 1884 la Federación Estadounidense de Sindicatos Organizados exigió una jornada laboral de ocho horas. Esto dio lugar a una huelga general y al alboroto de Haymarket de 1886. En el lado de la policía una bomba explotó. Fueron heridos 67 policías, de los cuales siete murieron. La policía abrió fuego, mató a varios hombres e hirió a 200. La tragedia de Haymarket pasó a formar parte de la historia de Estados Unidos.

What is International Worker's or May Day? The Bloody Story

The holiday may also be known as Labour Day or International Worker's Day and is marked with a public holiday in over 80 countries, but there is a bloody story of how May Day became a Holiday for Workers. The 1 May date is used because in 1884 the American Federation of Organized Trades Unions demanded an eight-hour workday, to come in effect as of 1 May 1886. This resulted in the general strike and the Haymarket Riot of 1886, a bomb exploded in the police ranks. It wounded 67 policemen, of whom seven died. The police opened fire, killing several men and wounding 200, and the Haymarket Tragedy became a part of U. S. history.

http://www.officeholidays.com/countries/global/may_day.php

http://time.com/3836834/may-day-labor-history/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Workers%27_Day

http://aattp.org/read-the-real-bloody-and-amazing-story-of-labor-day/

jueves, 27 de abril de 2017

Un Cortijo en Málaga, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, una ciudadana modelo

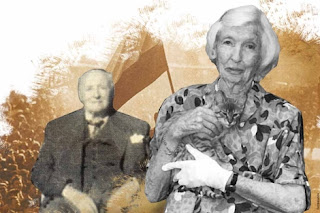

Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson (Eastbourne, Inglaterra, 6 de mayo de 1908 - Málaga, España, 12 de abril de 2003). Nació en Eastbourne pero pasó más de la mitad de su vida en Málaga. Hija de un abogado, George William Grice-Hutchinson. Su educación primaria fue informal, pero aprendió varios idiomas. En 1924 su padre adquirió una finca (San Julián) en la provincia de Málaga y luego pasó temporadas en España. Aquí, Marjorie fue testigo del estallido de la Guerra Civil (1936), y junto con su padre ayudó a huir a muchos españoles a Gibraltar en su barco, trayendo a su regreso medicinas y comida para la gente de Churriana (Málaga). Ambos colaboraron en actividades filantrópicas tales como el mantenimiento de la ayuda médica y una escuela en Churriana.

En 1941 trabajó para el Foreign Office y fue profesora en la Universidad de Londres, en King's College, y luego directora del Departamento de Español en el Birkbeck College. Durante ese tiempo estudió en la London School of Economics, obteniendo matrícula de honor. Allí fue discípula de R.S.Sayers y de Friedrich August von Hayeck (1899-1992), Premios Nobel de Economía en 1974, Hayeck dirigió su tesis doctoral.

Marjorie se estableció en la década de 1950, después de su matrimonio con el Barón Ulrich von Schlippenbach (ingeniero agrónomo), en Málaga. No tuvo hijos, pero publicó diferentes libros: Un cortijo en Málaga (1956), Los niños de la Vega: creciendo en un cortijo en España (1963), El Cementerio Inglés (1964), Early Economic Thought in Spain (1978), así como estudios económicos sobre Andalucía y muchos otros temas.

Marjorie fue amiga de Gerald Brenan y especialmente de su esposa Gamel Woolsey, con quien tenía muchas cosas en común como la pasión literaria y el amor a España. Se dice que Marjorie fue la responsable de que el libro de Gamel, Málaga en llamas, fuera traducido al español.

Es notable mencionar el trabajo social que realizó en Churriana después de la Guerra Civil y en 1984 donó la granja familiar "San Julián" a la Universidad de Málaga, donde se ubicó el Centro de Experimentación Grice-Hutchinson, durante los últimos años se encargó del Cementerio Inglés de Málaga, donde sería enterrada después de su muerte.

Así, Marjorie fue premiada por diferentes instituciones y universidades. En 1975 recibió la Orden del Imperio Británico (OBE) de Su Majestad, la Reina Isabel II. Marjorie también recibió la medalla Ateneo de Málaga y fue declarada "hija adoptiva" de Málaga.

Fuentes bibliográficas

Grice-Hutchinson, M. (1956). Malaga Farm. London: Hollis & Carter.

Grice-Hutchinson, M. (2016). Un cortijo en Málaga. A. Arenas y E. Girón (trad.). Málaga: Ediciones del Genal.

[Recuperado 27/04/2017] https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marjorie_Grice-Hutchinson

Málaga Farm, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson (A Model Citizen)

Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson (Eastbourne, England, 6 May 1908 – Málaga, Spain, 12 April 2003). She was born in Eastbourne, but spent over half her life in Málaga. She was the daughter of a lawyer, George William Grice-Hutchinson. Her primary education was informal, but she learned several languages. In 1924 her father acquired a farm (San Julián) in the province of Málaga and then she spent seasons in Spain. Here, Marjorie was witness to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, and with her father helped fleeing Spaniards to Gibraltar on their boat, bringing back medicine and food for the people of Churriana (Málaga).They collaborated in philanthropic activities such as the maintenance of medical help and a school in Churriana.

In 1941 she worked for the Foreign Office as a professor at the University of London, at King's College, then as director of the Spanish Department at Birkbeck College. During that time she studied at the London School of Economics, obtaining a degree honor. There she was a disciple of R.S.Sayers and of Friedrich August von Hayek (1899-1992), Nobel Prize of Economy in 1974, who directed her doctoral thesis.

Marjorie set permanently in the 1950s after her marriage to Baron Ulrich von Schlippenbach, an agronomist. She did not have any children and she continued her writing, publishing Malaga Farm (1956), Children of the Vega: Growing up on a Farm in Spain (1963), The English Cemetery (1964), Early Economic Thought in Spain (1978), as well as economic studies on Andalucia and many other subjects.

She forged a friendship with Gerald Brenan and especially with his wife Gamel Woolsey, with whom she had many things in common: literary passion and love of Spain. It is said Marjorie pushed for Gamel's book Malaga Burning to be translated into Spanish.

It is remarkable to mention the social work she carried out in Churriana after the Civil War and in 1984 she donated the family farm "San Julián" to the University of Málaga, where it was located the Grice-Hutchinson Experimentation Center "(Botanical Garden of the University of Málaga). During her last years she took care of the English Cemetery of Málaga, where she would receive burial after her death.

So, Marjorie was awarded by different institutions and universities. In 1975 she received an OBE from her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II. Marjorie was also awarded the Ateneo de Málaga Medal and was declared "Adopted Daughter".

Bibliographical sources

Grice-Hutchinson, M. (1956). Malaga Farm. London: Hollis & Carter.

Grice-Hutchinson, M. (2016). Un cortijo en Málaga. A. Arenas y E. Girón (trad.). Málaga: Ediciones del Genal.

[Recuperado 27/04/2017] https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marjorie_Grice-Hutchinson

domingo, 23 de abril de 2017

Dora Carrington: The Impossible Love That Inspired Brenan

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) was a British artist. Carrington was the daughter of a merchant from Liverpool and she considered that her family was very suffocating, especially her mother, who did not let her express herself freely. Dora found her escape valve in the art world, so she studied in London at the Slade School of Art. Although she was not a famous painter, she came into contact with artists, intellectuals and bohemians, who discovered in her a source of inspiration. Carrington was a woman unusual for her time because of her ideas, concerns and modern lifestyle. Dora was subjugated by biographer Lytton Strachey, eminent member of the Bloomsbury Circle (its name comes from the London borough where they met). This group was formed by an elite of British intellectuals. The ideology was liberal, enlightened, humanist and atheist. It was based on pacifism and free love. However, at that time, the Sex Offenses Act (1885) was very strict in the United Kingdom (the decriminalization of consensual homosexual practices, only in private, was passed in 1967). And after the condemnation of Oscar Wilde, the British homosexuals chose to control their manners in public. Many chose other countries more tolerant of their sexual practices.

Brenan could not easily forget Dora, he talks a lot about this painful relationship, which marks his literary production, and so that Carrington becomes the unavailable muse to whom the disdained poet sings. However, the romantic Brenan does not think about death, but on his future and he develops his own circle that will have its headquarters in Spain. Although his position with regard to sexuality is not clear, he had only one daughter with a domestic servant of Yegen: Juliana (1930) and went to live with the American poetess Gamel Woolsey, they adopted to Miranda Helen (who never met her biological mother). The author does not hesitate to refer to other romantic adventures of the couple that fit the open philosophy of the intellectuals with whom they were linked.

Bibliographical sources

Brenan, G. (1974): Personal Record 1920-1972. London: Jonathan Cape.

Brenan, G. (2012): Diarios sobre Dora Carrington. C. Pránger (Ed.). Málaga: Confluencias.

Gretchen Holbrook, G. (1989). Carrington: A Life. New York: W.W. Norton & Co..

Hill, J. (1994). The Art of Dora Carrington. London: The Herbert Press Ltd.

Haycock, D. B. (2009). A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War. London: Old Street Publishing.

[Recuperado 20/04/2017] https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Carrington

Dora Carrington: el amor imposible que inspiró a Gerald Brenan

Dora Carrington (1893-1932) fue una pintora británica. Carrington era la hija de un comerciante de Liverpool y consideraba que su familia era muy sofocante, especialmente su madre, quien no la dejaba expresarse libremente. Dora encontró su válvula de escape, en el mundo del arte, por ello estudió en Londres en la Slade School of Art. Aunque no destacó, entró en contacto con artistas, intelectuales y bohemios, quienes descubrieron en ella una fuente de inspiración. Carrington era una mujer inusual para su época por sus ideas, inquietudes y estilo de vida moderno. Dora quedó subyugada por el biógrafo Lytton Strachey, eminente miembro del Círculo de Bloomsbury (su nombre procede del barrio de Londres donde se reunían). Este grupo estaba formado por una élite de intelectuales británicos. Su ideología era liberal ilustrada, humanista y atea. Estaba basada en el pacifismo y el amor libre. Sin embargo, en ese tiempo, la Ley de Delitos Sexuales (1885) era muy estricta en el Reino Unido (no fue aprobada la despenalización de las prácticas homosexuales solo en privado hasta 1967). Y tras la condena de Oscar Wilde, los homosexuales británicos optaron por guardar las apariencias en público. Muchos abandonaron su tierra y eligieron otros países más tolerantes con la libertad sexual.

Brenan conoció a Dora Carrington, y cayó bajo su embrujo. Sus relaciones sentimentales fueron más platónicas que físicas, ya que Dora abierta a otros amores, en contadas ocasiones correspondía a sus requerimientos y lo rechazaba, porque lo consideraba una amenaza para su libertad. Esta pasión amorosa imposible produjo mucho sufrimiento a Brenan, el cual aumentó cuando la pintora se casó con su mejor amigo, Ralph Partridge con la aprobación de Lytton Strachey. Los tres se fueron a vivir juntos. Brenan era invitado a unirse a la comunidad de vez en cuando, pero el hispanista con un carácter pasional chocaba con un grupo dominado por la racionalidad y el utilitarismo de su líder. Dora, años más tarde, sería abandonada por Ralph y se suicidaría en 1932 tras la muerte de Lytton. Ralph, a pesar de sus diferencias, sería amigo de Brenan hasta el final de su vida. Aunque Brenan no pudo olvidar fácilmente a Dora, y en sus diarios y obras habla de esta dolorosa relación que marca su producción literaria, y Carrington se convierte en la musa inasequible a la que canta el poeta desdeñado.

Sin embargo, Brenan no piensa en la muerte, sino en su futuro, y desarrolla su propio círculo que tendrá su sede en España. Aunque no queda clara su posición ante la sexualidad, él tuvo solo una hija con una asistenta de Yegen: Juliana (1930) y se fue a vivir con la poetisa americana Gamel Woolsey, con quien adopta a Helen Miranda (quien nunca conoció a su madre biológica). El autor no tiene inconveniente en hacer referencia a otras aventuras sentimentales de la pareja que encajan con la filosofía abierta de los intelectuales con quienes ellos se vinculaban.

Fuentes

Brenan, G. (1974): Personal Record 1920-1972. London: Jonathan Cape.

Brenan, G. (2012): Diarios sobre Dora Carrington. C. Pránger (Ed.). Málaga: Confluencias.

Gretchen Holbrook, G. (1989). Carrington: A Life. New York: W.W. Norton & Co..

Hill, J. (1994). The Art of Dora Carrington. London: The Herbert Press Ltd.

Haycock, D. B. (2009). A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War. London: Old Street Publishing.

martes, 4 de abril de 2017

The "Alboronía", delicacy from "One Thousand and One Nights or Arabian Nights", is the beginning of all Spanish meals called "pistos"

For the Spanish scholar Carlos Alvar, In Cervantes and the Religions, by the text we know that the Jews ate this stew that could be festive (celebrations). According to the Dictionary of Authorities (1726), this stew is served during the days when it is forbidden to eat meat. Christians ate it during Lent (Cuaresma)*. These data support the great vitality of the term in "the time of the three cultures", with the final hegemony of the Christian who denounced the converts, most of them had been accused of being infidels for a long time by their customs (culinary, hygiene, etc.). These ones betrayed them. So, we can understand the reason why in Spain, the Iberian pig is one of the most representative meats.

In the end, tomatoes and peppers from America were added to the traditional stew. They replaced some of the compromising Hebrew or Moorish ingredients (aubergine, onion, pumpkin, nuts, chickpeas, etc.), which facilitates the change of the name by another one from Latin. "The pisto" from the Latin: pistus (crushed), it possibly related to the final presence of the plate, without connotations, it was well accepted by the old and new Christians (1897 Gayangos Glos, old voices s / v: In Castile we call "alboronía" to "pisto"). In fact, the voice "pisto" has been imposed against alboronía gradually over time.

But "alboronía" is not equal to "pisto", is the principle (principĭum). The term, today, is published and has revived in the field of gastronomy, it is seeking to distinguish itself with voices that properly define indigenous dishes and highlight their history (Jewish-Arabic-Andalusian cuisine). In this case, it was widely documented by such illustrious writers as the Cordoban J. Valera, who has claimed the voice in different works: "There was an exquisite alboronia that the famous Baghdad cook who invented it, and he gave it the name of the beautiful Princess Alboran, he could celebrate it, if he lived again ."

http://ciudaddelastresculturastoledo.blogspot.com.es/2014/10/pisto-manchego-tesoro-gastronomico.htlm

Lent (Cuaresma)*: The period preceding Easter that in the Christian Church is devoted to fasting, abstinence, and penitence in commemoration of Christ's fasting in the wilderness. In the Western Church it runs from Ash Wednesday to Holy Saturday and so includes forty weekdays.

SOURCES

REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA: Recursos en línea, http://www.rae.es/recursos/diccionarios [Recuperado 3/3/15]

COROMINAS, J. (1974). Diccionario crítico etimológico de la lengua castellana. Volumen I, A-C., Editorial Gredos, Madrid.

ALVAR EZQUERRA, M. (1961-1973). Atlas lingüístico y etnográfico del andaluz (6 tomos). Madrid: Arcos.

ALCALÁ VENCESLADA, A (1951). Vocabulario andaluz. Madrid: Real información Academia española.

ÁLVAREZ CURIEL, F. (199). Vocabulario popular andaluz. Málaga: Arguval.

CERVANTES, M. (1749). Comedias y entremeses: La Gran Sultana. Madrid: Ed. Antonio Marín. [Consulta 27/02/2015]

DELICADO, F. (1528). La lozana andaluza. Venecia: Edición digital, Alicante, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2004. < http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/la-lozana-andaluza--1/>. [06/03/15]

VALERA, J. (1824-1905). Obras de D. Juan Valera. Madrid: Imprenta y Fundición M. Tello, 1887. [En línea] Edición digital, Alicante, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes: [Biblioteca de autor] [3/03/2015] <http://bib.cervantesvirtual.com/FichaObra.html?Ref=3806&portal=53.

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)